Ethical Considerations for Human Subject Research

Ethical practices are central to all scientific endeavors, guiding researchers in pursuing knowledge with integrity and responsibility. However, extra ethical considerations and measures should be taken when research involves human subjects. Ensuring participants’ well-being, dignity, and rights must be prioritized, demanding rigorous standards to protect them from harm and exploitation.

What defines Human Subjects Research?

The CFR 46 defines human subject as any living subject with whom a researcher (whether professional or student) engages directly to collect information or biospecimens, subsequently utilizing, studying, or analyzing these materials; or acquiring, utilizing, studying, analyzing, or generating identifiable private data or biospecimens.

In this context, intervention involves any physical procedures or subject/environment manipulations for data collection, interaction entails the communication or interpersonal contact between investigator and subject, and private information encompasses those provided for specific purposes within the context of the study but not intended for public disclosure (e.g., medical records), which can potentially link it to particular individuals directly or indirectly through coding systems, or when the characteristics allow others to re-identify individuals.

Certain activities may not be considered human subjects research, including:

Classroom projects and unfunded undergraduate theses: Involving data collection from living individuals for educational purposes, provided they stay within the classroom and are not intended for external use.

Quality improvement/assurance activities and program evaluations: Conducted internally to measure program effectiveness or improvement, such as teaching or curriculum evaluations.

Use of de-identified or coded private information: Where the research team cannot readily ascertain the identities of individuals and certain conditions are met regarding the handling of coded information.

Case reports: Limited to describing clinical features and outcomes of a single patient without involving systematic investigation.

Fact-collecting interviews: Focused on things, products, or policies rather than individuals’ opinions, behaviors, characteristics, or experiences.

Biographies or autobiographies: Involving interviews with living individuals about their experiences, limited to that individual and not intended to be generalized beyond them.

Even though the types of studies listed above are typically not considered human subject research, it is always important to check with your campus Institutional Review Board (IRB) or Research Integrity Office for a formal determination on whether your study qualifies as human subject research.

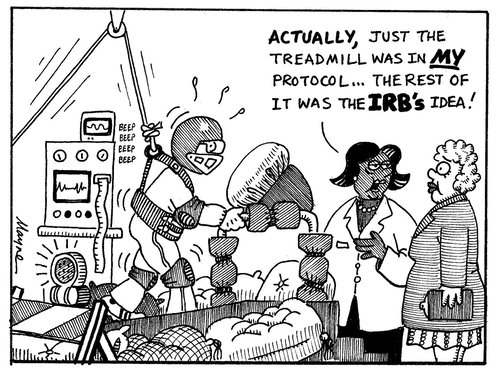

Jokes aside, IRB boards are tasked with guaranteeing the complete protection of the rights and welfare of research participants through ethical oversight and by monitoring compliance with regulations. Most importantly, you should NOT start a project or pilot study before obtaining a formal determination from the IRB or Research Integrity Office. This is crucial to ensure you are in compliance with all relevant regulations and ethical guidelines for research involving human participants.

At UCSB, researchers should fill out this checklist and follow the submission instructions outlined in the form. Ensure to check specific guidelines and policies at your institution.

If it’s determined that the study constitutes human subject research, we will cover additional steps shortly. But first, let’s understand the purpose of IRBs.

Why are IRBs not only important but also required?

Institutional review boards (IRBs) are federally mandated to review research involving human subjects, ensuring proposed protocols meet ethical guidelines before enrollment. IRBs emerged as a means to prevent unethical behavior and adverse risks to participants and to ensure the protection of the welfare of individuals participating in research.

Before the establishment of IRBs there was no formal oversight of the ethical conduct of research with regard to human subjects, which could expose unwary participants to physical and psychological risks. Also, vulnerable groups and economically or educationally disadvantaged groups could be targeted for exploitation. Some infamous examples were the Milgram’s Obedience/Authority study (1961), the Stanford Prison Experiment (1971) and the Tuskegee syphilis study (1931 to 1972). The common thread in these studies was a blatant disregard for the ethical principles of respect for persons, beneficence, and justice in human subjects research. Participants were exploited, deceived, and subjected to significant harm, all in the name of research.

These egregious violations of research ethics led to the development of key guidelines and regulations, such as the Belmont Report and the Common Rule (last updated in 2018), to protect human research participants.

The history of IRBs in the U.S. traces back to 1974, when the National Research Act was signed, creating the National Commission for the Protection of Human Subjects of Biomedical and Behavioral Research.The publication of the Belmont Report in 1979 provided the moral and ethical framework for human subjects research. It was through the Belmont Report that the basic principles of beneficence, respect of persons, and justice in the context of informed consent, assessment of risks and benefits and selection of human subjects were first formally outlined, which later led to the development of regulations, such as the Common Rule (signed initially in 1991 and last updated in 2018), to protect human research participants in the United States.

We encourage you to watch the video below for a better introduction on what IRBs are and how they serve to protect human subjects:

Source: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (2018)

Types of IRB Review

If your research qualifies as human subject you must go through a IRB review. The type of IRB review required depends on the level of risk to participants and the specific characteristics of the research project. Researchers cannot make the determination themselves, and must submit their project to the IRB for the appropriate level of review.

Exempt: Exempt studies include research in educational settings, surveys/interviews of public behavior, and analysis of pre-existing data/specimens. These studies are not monitored by the IRB, but the ethical principles of human subjects research still apply.

Expedite Review: An expedited review does not mean a faster turnaround, but rather that the project can be reviewed by a single IRB member rather than the full board. A research project that can potentially pose minimal risk to participants is classified under this category.

Full Review: This is required for studies involving controlled substances, devices, or requiring human biological specimens. Studies that anticipate any procedures that might cause physical harm or any significant psychological distress. It also applies to research on highly sensitive topics (e.g., sexual abuse, suicide, etc.) or with vulnerable populations (e.g., prisoners, illegal immigrants).

It is never too much to emphasize that researchers cannot self-determine which category their research belongs to, and all research with human subjects should be reviewed by the local IRB. For more information, consult the Office of Research’s For Researchers in Human Subjects page. Also, researchers are required to complete mandatory IRB training (https://orahs.research.ucsb.edu) before engaging in research with human participants.

The Role of Consent Forms

All research with human participants, including exempted, should ask participants to confirm their agreement. However, signed consent forms or waivers are only requested for expedited and full review studies.

The informed consent process is a central component of the ethical conduct of research with human subjects overseen by an Institutional Review Board (IRB). It ensures individuals have an informed choice about participating in a research study. In the United States, several regulations and policies stipulate the requirements for obtaining informed consent from research participants.

It is beyond the scope of this course to go through the steps of developing or analyzing consent forms. Such forms are highly contextual to the research and the nature of the study. Nonetheless, here is an example from the UCSB Office of Research for illustrative purposes, and essentially, we advise researchers to incorporate the items below:

A declaration indicating that the study constitutes research, accompanied by elucidating the research’s essence and objectives.

A description of the procedures to be employed and an estimation of the duration of the subject’s involvement.

A declaration outlining the degree to which the confidentiality of records identifying the subjects will be upheld.

A statement regarding the potential removal of identifiers from identifiable private information or biospecimens, enabling their utilization in future research without necessitating additional informed consent. Or a statement asserting that information or biospecimens collected in this research, even post-identifier removal, will not be utilized for subsequent research endeavors.

A description of any conceivable discomforts and risks that could reasonably be anticipated, or exceptionally, a mention that there are no foreseeable risks.

An explanation of any benefits, either to the subject or to society, that could reasonably be expected from the research (note that remuneration or class credit is not deemed a benefit).

An invitation to address any questions/concerns regarding the study.

An affirmation that participation is voluntary, emphasizing that refusal to participate will incur no penalty or forfeiture of entitled benefits and that the subject retains the right to discontinue participation at any point without consequence.

An explication of whom to contact for research information, including the investigator’s name, telephone number, and email address.

Contact information provided for clarification regarding the rights of research subjects.

Consent for Photographs or Recordings

Consent forms for studies involving audio, video recordings, or photographs, should include the following:

A description of which recording technology will be used and with what purpose.

The type and extent of identifiable information that will be captured and retained and how the recorded data will be stored, secured, used, and destroyed.

A clear statement requesting confirmation and accounting for the use of excerpts in academic and teaching materials.

For this last, we recommend you add tiered options, as described below:

| Example 1: Recording | I consent to this interview being audio-recorded for transcription purposes. Y____ N ____ |

| Example 2: Use/Reuse | I consent to de-identified excerpts of my interview to be used in academic publications. Y____ N ____ I consent to de-identified excerpts of my interview to be used in classroom activities. Y____ N ____ | |

| Example 3: Sharing | I consent audio recordings to be shared with select research teams. Y____ N ____ I consent audio recordings to be shared on a protected repository available to verified researchers. Y____ N ____ I consent audio recordings to be shared on a repository with unvetted public access. Y____ N____ |

Consent for Data Sharing and Re-use

Many funding agencies and publishers now require researchers to share their data to promote future reuse and application, including data from qualitative research. Consequently, it is crucial for investigators to carefully address these requirements when developing consent forms that allow for data sharing and reuse. Researchers should clearly outline their plans for managing, using, and sharing data, ensuring participants fully understand these processes.

Consent forms should specify how data will be shared and published, detailing the types of data to be shared and the methods of dissemination. They should also include explicit provisions for potential future reuse.

Importantly, raw unprocessed recordings or unidentified transcripts typically are not shareable and won’t be accepted by a data repository. If private or sensitive identifying information is collected, it must be de-identified before sharing. Additionally, if data will be shared without access controls, the consent form should clearly state that the data may be reused by other researchers for purposes beyond those initially described in the study.

In practice, here is how a statement accounting for sharing and potential reuse could look like the following:

✍️ “Upon the completion of the project, we plan to archive de-identified interview transcripts, ensuring they remain unlinked to individuals, at [data repository name and link]. These datasets will be openly accessible for reuse by repository users for research or educational purposes, which may differ from those outlined in this study.”

This handout provides a compilation of helpful tips:

Source: UCSB Library Data Literacy Series (perma.cc/U4D8-UYFR).

Alignment with repository access policies: Ensure consent language supports options for data deposition (controlled or public) supported by the repository of your choice.

Modular Consent: You may also consider creating flexible consent language to adjust future data sharing options and obtain separate signatures for different uses.

Documentation: Keep consent documentation with the data to inform future users of participant agreements.

Don’t worry to memorize all this now! We will recap some of these considerations later on data sharing and archiving episode.

Recommended/Cited Sources:

Cychosz M, Romeo R, Soderstrom M, Scaff C, Ganek H, Cristia A, Casillas M, de Barbaro K, Bang JY, Weisleder A. Longform recordings of everyday life: Ethics for best practices. Behav Res Methods. 2020 Oct;52(5):1951-1969. doi: 10.3758/s13428-020-01365-9. PMID: 32103465; PMCID: PMC7483614.

ICPSR (2024). Recommended Informed Consent Language for Data Sharing: https://perma.cc/Q4JE-8G9F

UIUC (2022). Representing Data Sharing in Informed Consent: Guidance for Researchers at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign: https://perma.cc/5MQG-FKJB

VandeVusse, A., Mueller, J., & Karcher, S. (2022). Qualitative data sharing: Participant understanding, motivation, and consent. Qualitative Health Research, 32(1), 182-191. doi: 10.1177/10497323211054058.