Making Plots With plotnine

Overview

Teaching: 40 min

Exercises: 50 minQuestions

How can I visualize data in Python?

What is ‘grammar of graphics’?

Objectives

Create a

plotnineobject.Set universal plot settings.

Modify an existing plotnine object.

Change the aesthetics of a plot such as color.

Edit the axis labels.

Build complex plots using a step-by-step approach.

Create scatter plots, box plots, and time series plots.

Use the facet_wrap and facet_grid commands to create a collection of plots splitting the data by a factor variable.

Create customized plot styles to meet their needs.

Disclaimer

Python has powerful built-in plotting capabilities such as matplotlib, but for

this episode, we will be using the plotnine

package, which facilitates the creation of highly-informative plots of

structured data based on the R implementation of ggplot2

and The Grammar of Graphics

by Leland Wilkinson. The plotnine

package is built on top of Matplotlib and interacts well with Pandas.

Reminder

plotnineis not included in the standard Anaconda installation and needs to be installed separately. If you haven’t done so already, you can find installation instructions on the Setup page.

Just as with the other packages, plotnine needs to be imported. It is good

practice to not just load an entire package such as from plotnine import *,

but to use an abbreviation as we used pd for Pandas:

%matplotlib inline

import plotnine as p9

From now on, the functions of plotnine are available using p9.. For the

exercise, we will use the surveys.csv data set, with the NA values removed

import pandas as pd

surveys_complete = pd.read_csv('data/surveys.csv')

surveys_complete = surveys_complete.dropna()

Plotting with plotnine

The plotnine package (cfr. other packages conform The Grammar of Graphics) supports the creation of complex plots from data in a

dataframe. It uses default settings, which help creating publication quality

plots with a minimal amount of settings and tweaking.

plotnine graphics are built step by step by adding new elements adding

different elements on top of each other using the + operator. Putting the

individual steps together in brackets () provides Python-compatible syntax.

To build a plotnine graphic we need to:

- Bind the plot to a specific data frame using the

dataargument:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete))

As we have not defined anything else, just an empty figure is available and presented.

- Define aesthetics (

aes), by selecting variables used in the plot andmappingthem to a presentation such as plotting size, shape, color, etc. You can interpret this as: which of the variables will influence the plotted objects/geometries:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight', y='hindfoot_length')))

The most important aes mappings are: x, y, alpha, color, colour,

fill, linetype, shape, size and stroke.

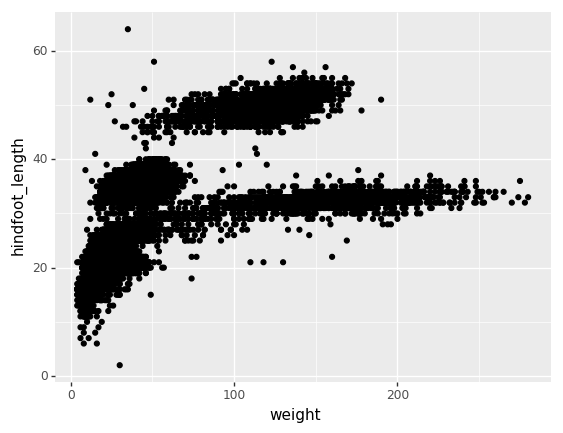

- Still no specific data is plotted, as we have to define what kind of geometry

will be used for the plot. The most straightforward is probably using points.

Points is one of the

geomsoptions, the graphical representation of the data in the plot. Others are lines, bars,… To add a geom to the plot use+operator:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight', y='hindfoot_length'))

+ p9.geom_point()

)

The + in the plotnine package is particularly useful because it allows you

to modify existing plotnine objects. This means you can easily set up plot

templates and conveniently explore different types of plots, so the above

plot can also be generated with code like this:

# Create

surveys_plot = p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight', y='hindfoot_length'))

# Draw the plot

surveys_plot + p9.geom_point()

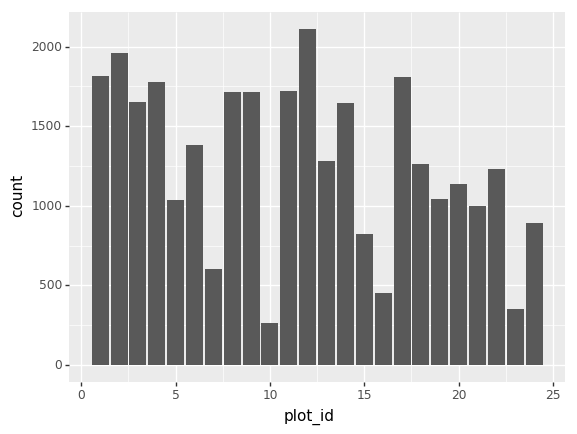

Challenge - bar chart

Working on the

surveys_completedata set, use theplot-idcolumn to create abar-plot that counts the number of records for each plot. (Check the documentation of the bar geometry to handle the counts)Answers

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete, mapping=p9.aes(x='plot_id')) + p9.geom_bar() )

Notes:

- Anything you put in the

ggplot()function can be seen by any geom layers that you add (i.e., these are universal plot settings). This includes thexandyaxis you set up inaes(). - You can also specify aesthetics for a given

geomindependently of the aesthetics defined globally in theggplot()function.

Building your plots iteratively

Building plots with plotnine is typically an iterative process. We start by

defining the dataset we’ll use, lay the axes, and choose a geom. Hence, the

data, aes and geom-* are the elementary elements of any graph:

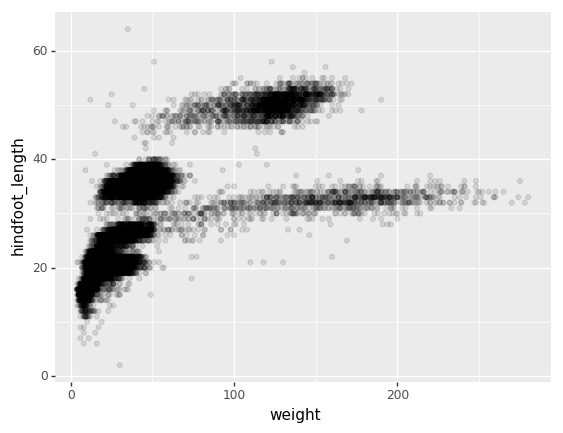

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight', y='hindfoot_length'))

+ p9.geom_point()

)

Then, we start modifying this plot to extract more information from it. For instance, we can add transparency (alpha) to avoid overplotting:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight', y='hindfoot_length'))

+ p9.geom_point(alpha=0.1)

)

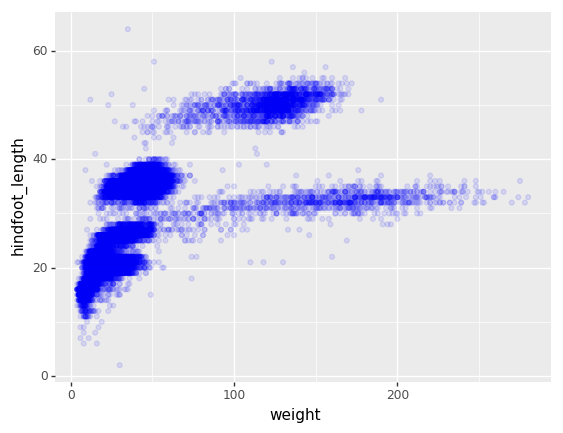

We can also add colors for all the points

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight', y='hindfoot_length'))

+ p9.geom_point(alpha=0.1, color='blue')

)

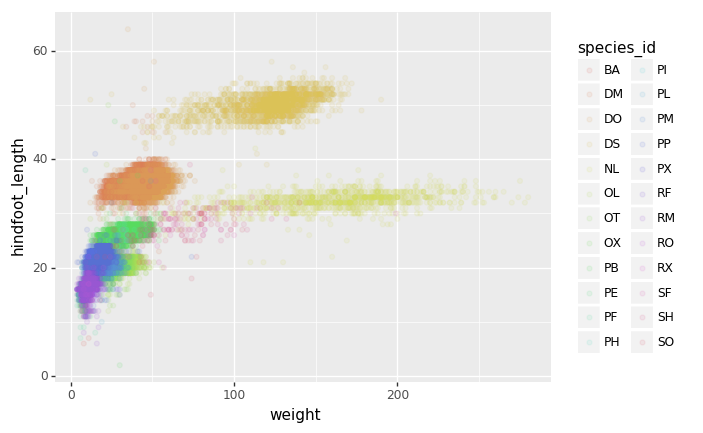

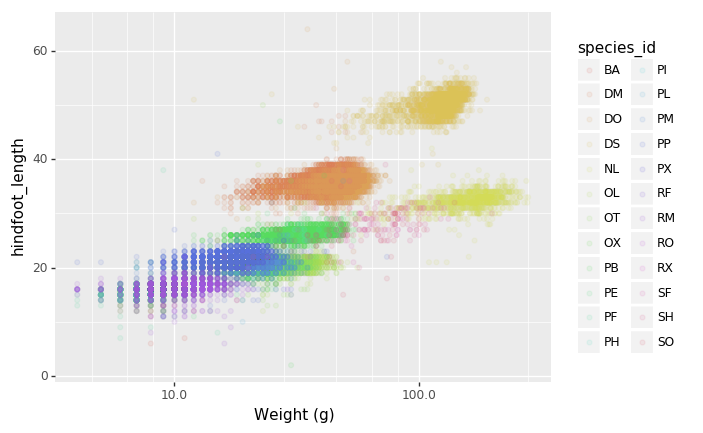

Or to color each species in the plot differently, map the species_id column

to the color aesthetic:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight',

y='hindfoot_length',

color='species_id'))

+ p9.geom_point(alpha=0.1)

)

Apart from the adaptations of the arguments and settings of the data, aes

and geom-* elements, additional elements can be added as well, using the +

operator:

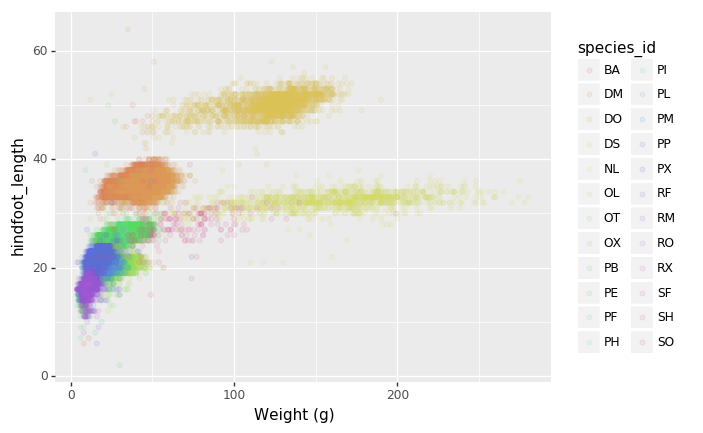

- Changing the labels:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight', y='hindfoot_length', color='species_id'))

+ p9.geom_point(alpha=0.1)

+ p9.xlab("Weight (g)")

)

- Defining scale for colors, axes,… For example, a log-version of the x-axis could support the interpretation of the lower numbers:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight', y='hindfoot_length', color='species_id'))

+ p9.geom_point(alpha=0.1)

+ p9.xlab("Weight (g)")

+ p9.scale_x_log10()

)

- Changing the theme (

theme_*) or some specific theming (theme) elements. Usually plots with white background look more readable when printed. We can set the background to white using the functiontheme_bw().

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight', y='hindfoot_length', color='species_id'))

+ p9.geom_point(alpha=0.1)

+ p9.xlab("Weight (g)")

+ p9.scale_x_log10()

+ p9.theme_bw()

+ p9.theme(text=p9.element_text(size=16))

)

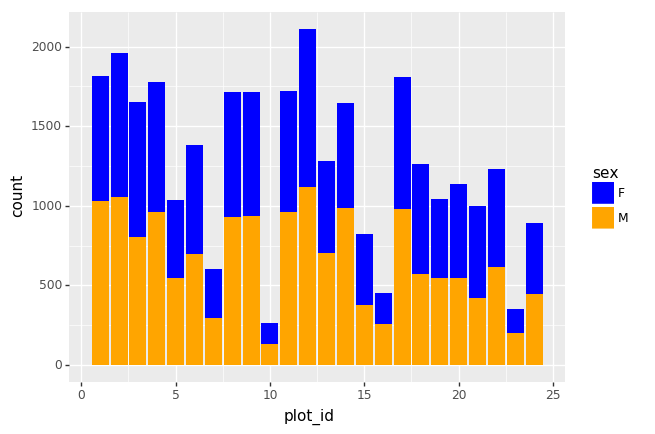

Challenge - Bar plot adaptations

Adapt the bar plot of the previous exercise by mapping the

sexvariable to the color fill of the bar chart. Change thescaleof the color fill by providing the colorsblueandorangemanually (see API reference to find the appropriate function).Answers

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete, mapping=p9.aes(x='plot_id', fill='sex')) + p9.geom_bar() + p9.scale_fill_manual(["blue", "orange"]) )

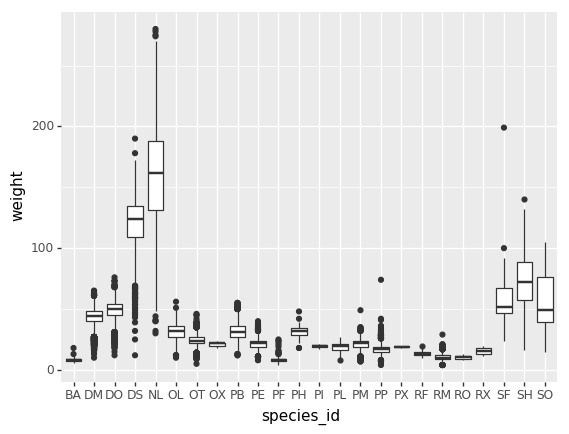

Plotting distributions

Visualizing distributions is a common task during data exploration and

analysis. To visualize the distribution of weight within each species_id

group, a boxplot can be used:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='species_id',

y='weight'))

+ p9.geom_boxplot()

)

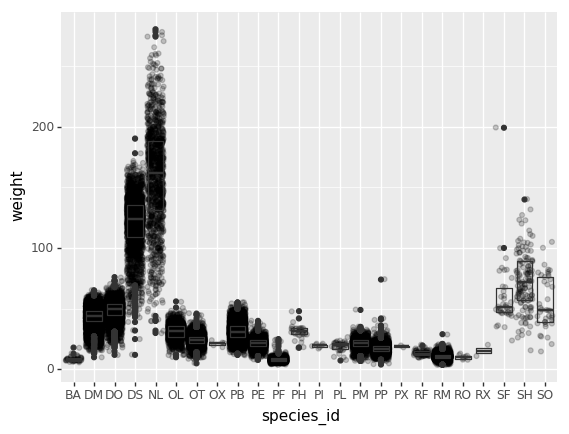

By adding points of the individual observations to the boxplot, we can have a better idea of the number of measurements and of their distribution:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='species_id',

y='weight'))

+ p9.geom_jitter(alpha=0.2)

+ p9.geom_boxplot(alpha=0.)

)

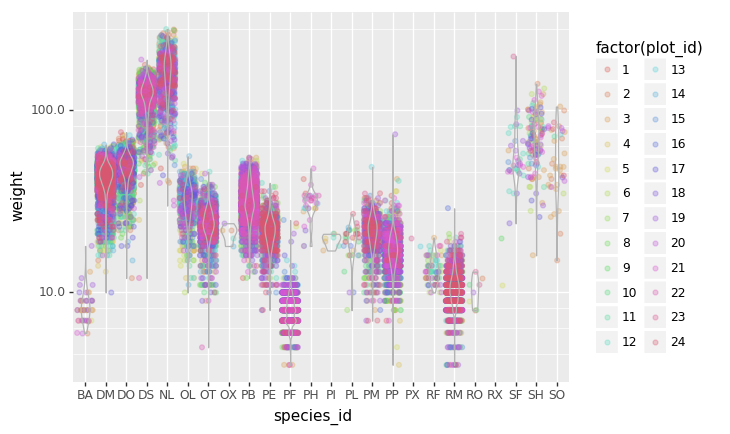

Challenge - distributions

Boxplots are useful summaries, but hide the shape of the distribution. For example, if there is a bimodal distribution, this would not be observed with a boxplot. An alternative to the boxplot is the violin plot (sometimes known as a beanplot), where the shape (of the density of points) is drawn.

In many types of data, it is important to consider the scale of the observations. For example, it may be worth changing the scale of the axis to better distribute the observations in the space of the plot.

- Replace the box plot with a violin plot, see

geom_violin()- Represent weight on the log10 scale, see

scale_y_log10()- Add color to the datapoints on your boxplot according to the plot from which the sample was taken (

plot_id)Hint: Check the class for

plot_id. By usingfactor()within theaesmapping of a variable,plotninewill handle the values as category values.Answers

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete, mapping=p9.aes(x='species_id', y='weight', color='factor(plot_id)')) + p9.geom_jitter(alpha=0.3) + p9.geom_violin(alpha=0, color="0.7") + p9.scale_y_log10() )

Data Moment

Communicate your data more effectively

When communicating your data visually, you should consider the best alternatives available for the type of data at hand. Data visualizations should make it easier for the audience to quickly understand the information presented and evaluate the outcomes from that data. They should be practical, appealing, and, most and foremost, accurate. Therefore, it is vital to consider the advantages and limitations of different graphs. For example, on the one hand, box plots help represent various statistics from a large amount of data in a single box plot, display the range and distribution of data along a number line, and provide some indication of the data’s symmetry and skewness, and show outliers. On the other hand, they have some pitfalls, as they may hide the multimodality and other features of distributions, they can be only used for numerical data, and can’t represent means and modes. Make sure to always weigh the cons and pros of each graphing option before making a decision.

Data Moment

Data Documentation

Data documentation is vital; without it, data has no meaning. Documentation should include the data’s overall intent and purpose and how it was gathered or measured. For tabular data such as we are working with here, documentation should include the meaning of the rows and the definitions of the columns, including units of measure, missing values, and any special codes. Some data formats support placing the documentation inside the file; unfortunately, CSV does not. Therefore, documentation for this data format should be placed in a separate (but co-located) README file see a customizable template here or use a metadata standard such as DDI.

Data Moment

Accuracy and Precision

You may have noticed that in our data frame, weights are integer numbers of grams, but RStudio displays computed quantities such as

df$weight_lbusing many digits after the decimal point. Is that precision warranted? In a word, no. Accuracy refers to how close a value in the computer is to the true value. Precision refers to how precisely a value is displayed (roughly, how many digits are printed). The precision should ideally reflect the accuracy, but in any case should not exceed it. RStudio does not know the accuracy of your data, and hence displays a default number of a digits, i.e., a default precision, whether that precision is warranted or not. Thus it is normal to see many digits displayed while working with data. When presenting data, use the round function to adjust the digits displayed to reflect the data’s accuracy.

Data Moment

Ethics

Although we are using data that is under a CC-BY license, there still may be some ethical issues to consider before its use:

- Did the participants agree to have their data published?

- Even so, is it possible for people to be identified through the data in the way you are using it?

- What uses did the participants agree to for their data?

- Even though the data is itself released under a CC-BY license, is the use of SAFI data for Carpentry permissible under the original agreement?

- Is the use and reuse of this data in any setting beyond the scope or conception of the participants?

- Is it ethical to use this data if so?

Data Moment

Licensing

In any data project, it is critical to understand the licenses that govern the use and reuse of the data. See here our primer on what software and data licenses are and how they can impact your use of data.

This module uses the following data:

Title: SAFI Survey Results Project License: CC-BY About: The SAFI Project is a research project looking at farming and irrigation methods used by farmers in Tanzania and Mozambique. This dataset is composed of survey data relating to households and agriculture in Tanzania and Mozambique. The survey form was created using the ODK (Open Data Kit) software via an Excel spreadsheet. This is used to create a form which can be downloaded and displayed (and completed) on an Android smartphone. The results are then sent back to a central server. The server can be used to produce the collected data in both JSON and CSV formats.

———–REMOVE

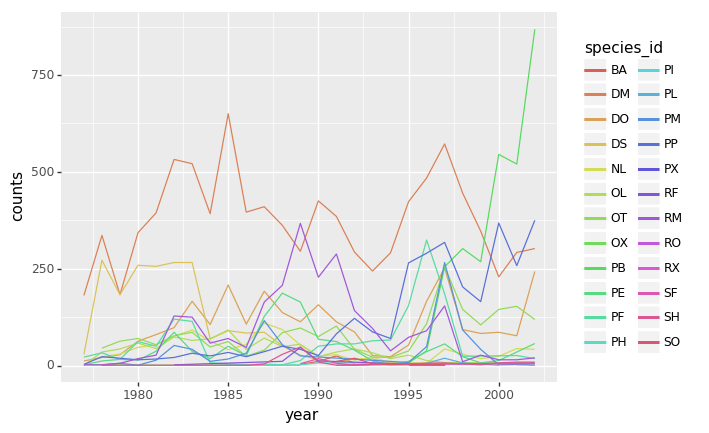

Plotting time series data

Let’s calculate number of counts per year for each species. To do that we need

to group data first and count the species (species_id) within each group.

yearly_counts = surveys_complete.groupby(['year', 'species_id'])['species_id'].count()

yearly_counts

When checking the result of the previous calculation, we actually have both the

year and the species_id as a row index. We can reset this index to use both

as column variable:

yearly_counts = yearly_counts.reset_index(name='counts')

yearly_counts

Timelapse data can be visualised as a line plot (geom_line) with years on x

axis and counts on the y axis.

(p9.ggplot(data=yearly_counts,

mapping=p9.aes(x='year',

y='counts'))

+ p9.geom_line()

)

Unfortunately this does not work, because we plot data for all the species

together. We need to tell plotnine to draw a line for each species by

modifying the aesthetic function and map the species_id to the color:

(p9.ggplot(data=yearly_counts,

mapping=p9.aes(x='year',

y='counts',

color='species_id'))

+ p9.geom_line()

)

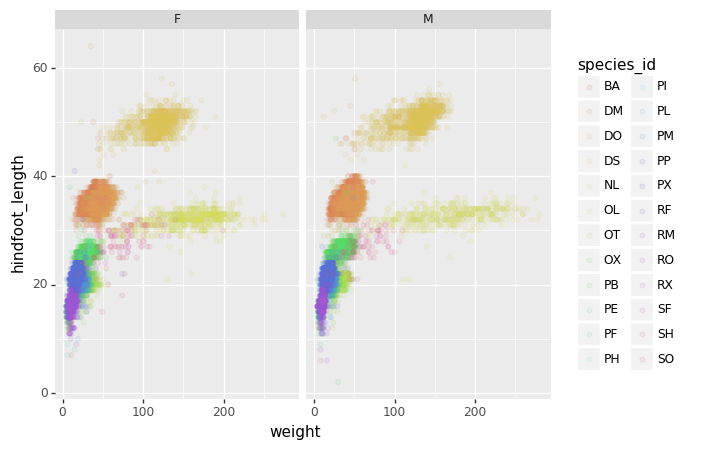

Faceting

As any other library supporting the Grammar of Graphics, plotnine has a

special technique called faceting that allows to split one plot into multiple

plots based on a factor variable included in the dataset.

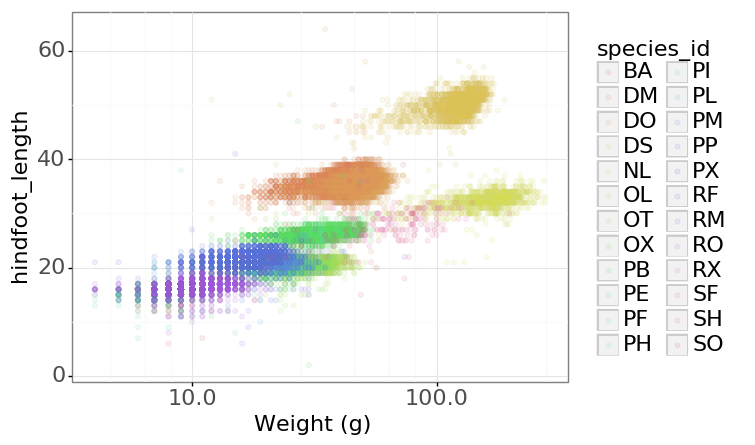

Consider our scatter plot of the weight versus the hindfoot_length from the

previous sections:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight',

y='hindfoot_length',

color='species_id'))

+ p9.geom_point(alpha=0.1)

)

We can now keep the same code and at the facet_wrap on a chosen variable to

split out the graph and make a separate graph for each of the groups in that

variable. As an example, use sex:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight',

y='hindfoot_length',

color='species_id'))

+ p9.geom_point(alpha=0.1)

+ p9.facet_wrap("sex")

)

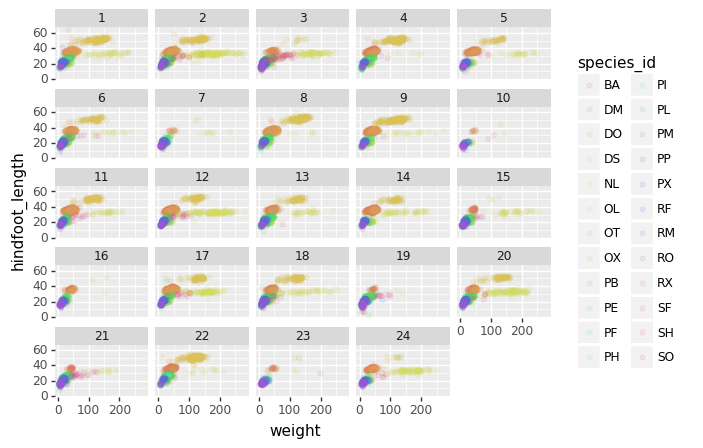

We can apply the same concept on any of the available categorical variables:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight',

y='hindfoot_length',

color='species_id'))

+ p9.geom_point(alpha=0.1)

+ p9.facet_wrap("plot_id")

)

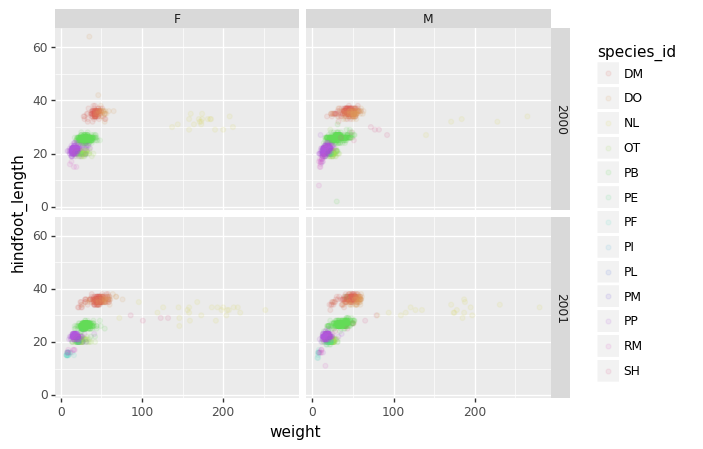

The facet_wrap geometry extracts plots into an arbitrary number of dimensions

to allow them to cleanly fit on one page. On the other hand, the facet_grid

geometry allows you to explicitly specify how you want your plots to be

arranged via formula notation (rows ~ columns; a . can be used as a

placeholder that indicates only one row or column).

# only select the years of interest

survey_2000 = surveys_complete[surveys_complete["year"].isin([2000, 2001])]

(p9.ggplot(data=survey_2000,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight',

y='hindfoot_length',

color='species_id'))

+ p9.geom_point(alpha=0.1)

+ p9.facet_grid("year ~ sex")

)

Challenge - facetting

Create a separate plot for each of the species that depicts how the average weight of the species changes through the years.

Answers

yearly_weight = surveys_complete.groupby(['year', 'species_id'])['weight'].mean().reset_index() (p9.ggplot(data=yearly_weight, mapping=p9.aes(x='year', y='weight')) + p9.geom_line() + p9.facet_wrap("species_id") )

Challenge - facetting

Based on the previous exercise, visually compare how the weights of male and females has changed through time by creating a separate plot for each sex and an individual color assigned to each

species_id.Answers

yearly_weight = surveys_complete.groupby(['year', 'species_id', 'sex'])['weight'].mean().reset_index() (p9.ggplot(data=yearly_weight, mapping=p9.aes(x='year', y='weight', color='species_id')) + p9.geom_line() + p9.facet_wrap("sex") )

Further customization

As the syntax of plotnine follows the original R package ggplot2, the

documentation of ggplot2 can provide information and inspiration to customize

graphs. Take a look at the ggplot2 cheat sheet, and think of ways to

improve the plot. You can write down some of your ideas as comments in the Etherpad.

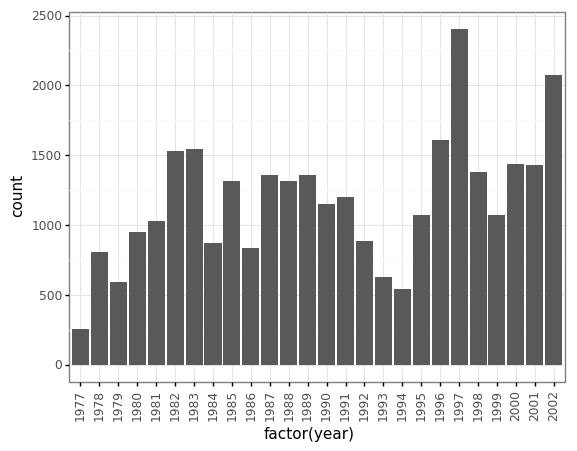

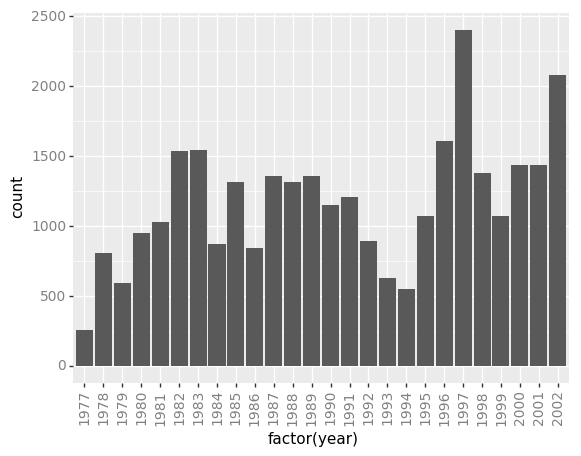

The theming options provide a rich set of visual adaptations. Consider the following example of a bar plot with the counts per year.

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='factor(year)'))

+ p9.geom_bar()

)

Notice that we use the year here as a categorical variable by using the

factor functionality. However, by doing so, we have the individual year

labels overlapping with each other. The theme functionality provides a way to

rotate the text of the x-axis labels:

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='factor(year)'))

+ p9.geom_bar()

+ p9.theme_bw()

+ p9.theme(axis_text_x = p9.element_text(angle=90))

)

When you like a specific set of theme-customizations you created, you can save them as an object to easily apply them to other plots you may create:

my_custom_theme = p9.theme(axis_text_x = p9.element_text(color="grey", size=10,

angle=90, hjust=.5),

axis_text_y = p9.element_text(color="grey", size=10))

(p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='factor(year)'))

+ p9.geom_bar()

+ my_custom_theme

)

Challenge - customization

Please take another five minutes to either improve one of the plots generated in this exercise or create a beautiful graph of your own.

Here are some ideas:

- See if you can change thickness of lines for the line plot .

- Can you find a way to change the name of the legend? What about its labels?

- Use a different color palette (see http://www.cookbook-r.com/Graphs/Colors_(ggplot2))

After creating your plot, you can save it to a file in your favourite format.

You can easily change the dimension (and its resolution) of your plot by

adjusting the appropriate arguments (width, height and dpi):

my_plot = (p9.ggplot(data=surveys_complete,

mapping=p9.aes(x='weight', y='hindfoot_length'))

+ p9.geom_point()

)

my_plot.save("scatterplot.png", width=10, height=10, dpi=300)

Key Points

The

data,aesvariables and ageometryare the main elements of a plotnine graphWith the

+operator, additionalscale_*,theme_*,xlab/ylabandfacet_*elements are added